ALTHOUGH the date of the introduction of the vine into France is lost in the mists of antiquity, and though the wines of Marseilles, Narbonne, and Vienne were celebrated by Roman writers prior to the Christian era, many centuries elapsed before a vintage was gathered within the limits of the ancient province of Champagne. Whilst the vine and olive throve in the sunny soil of the Narbonnese Gaul, the frigid climate of the as yet uncultivated North forbade the production of either wine or oil.[1] The ‘forest of the Marne,’ now renowned for the vintage it yields, was then indeed a dark and gloomy wood, the haunt of the wolf and wild boar, the stag and the auroch; and the tall barbarians of Gallia Comata, who manned the walls of Reims on the approach of Cæsar, were fain to quaff defiance to the Roman power in mead and ale.[2] Though Reims became under the Roman dominion one of the capitals of Belgic Gaul, and acquired an importance to which numerous relics in the shape of temples, triumphal arches, baths, arenas, military roads, &c., amply testify; and though the Gauls were especially distinguished by their quick adoption [Pg 2]of Roman customs, it appears certain that during the sway of the twelve Cæsars the inhabitants of the present Champagne district were forced to draw the wine, with which their amphoræ were filled and their pateræ replenished, from extraneous sources. The vintages of which Pliny and Columella have written were confined to Gallia Narboniensis, though the culture of the vine had doubtless made some progress in Aquitaine and on the banks of the Saône, when the stern edict of the fly-catching madman Domitian, issued on the plea that the plant of Bacchus usurped space which would be better filled by that of Ceres, led (A.D. 92) to its total uprooting throughout the Gallic territory.

For nearly two hundred years this strange edict remained in force, during which period all the wine consumed in the Gallo-Roman dominions was imported from abroad. Six generations of men, to whom the cheerful toil of the vine-dresser was but an hereditary tale, and the joys of the vintage a half-forgotten tradition, had passed away when, in 282, the Emperor Probus, a gardener’s son, once more granted permission to cultivate the vine, and even exercised his legions in the laying-out and planting of vineyards in Gaul.[3] The culture was eagerly resumed, and, as with the advancement of agriculture and the clearance of forests the climate had gradually improved, the inhabitants of the more northern regions sought to emulate their southern neighbours in the production of wine. This concession of Probus was hailed with rejoicing; and some antiquaries maintain that the triumphal arch at Reims, known as the Gate of Mars, was erected during his reign as a token of gratitude for this permission to replant the vine.[4]

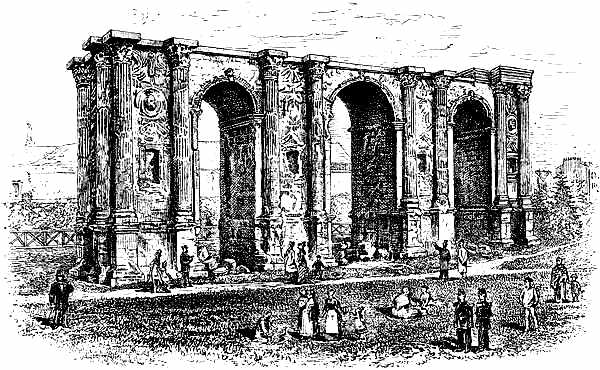

By the fourth century the banks of the Marne and the Moselle were clothed with vineyards, which became objects of envy and desire to the yellow-haired tribes of Germany,[5] and led in no small degree to the predatory incursions into the territory of Reims so severely repulsed by Julian the Apostate and the Consul Jovinus, who had aided Julian to ascend the throne of the Cæsars, and had combatted for him against the Persians. Julian assembled his forces at Reims in 356, before advancing against the Alemanni, who had established themselves in Alsace and Lorraine; and ten years later the Consul Jovinus, after surprising some of the same nation bathing their large limbs, combing their long and flaxen hair, and ‘swallowing huge draughts of rich and delicious wine,’[6] on the banks of the Moselle, fought a desperate and successful battle, lasting an entire summer’s day, on the Catalaunian plains near Châlons, with their comrades, whom the prospect of similar indulgence had tempted to enter the Champagne. Valerian came to Reims in 367 to congratulate Jovinus; and the Emperor and the Consul (whose tomb is to-day preserved in Reims Cathedral) fought their battles o’er again over their cups in the palace reared by the latter on the spot occupied in later years by the church of St. Nicaise.

THE GATE OF MARS AT REIMS.

The check administered by Jovinus was but temporary, while the attraction continued permanent. [Pg 4]For nearly half a century, it is true, the vineyards of the Champagne throve amidst an era of quiet and prosperity such as had seldom blessed the frontier provinces of Gaul.[7] But when, in 406, the Vandals spread the flame of war from the banks of the Rhine to the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the ocean, Reims was sacked, its fields ravaged, its bishop cut down at the altar, and its inhabitants slain or made captive; and the same scene of desolation was repeated when the hostile myriads of Attila swept across north-western France in 451.

TOMB OF THE CONSUL JOVINUS, PRESERVED IN REIMS CATHEDRAL.

Happier times were, however, in store for Reims and its bishops and its vineyards, the connection between the two last being far more intimate than might be supposed. When Clovis and his Frankish host passed through Reims by the road still known as the Grande Barberie, on his way to attack Syagrius in 486, there was no doubt a little pillaging, and the famous golden vase which one of the monarch’s followers carried off from the episcopal residence was not left unfilled by its new owner. But after Syagrius had been crushed at Soissons, and the theft avenged by a blow from the king’s battle-axe, Clovis not only restored the stolen vase, and made a treaty with the bishop St. Remi or Remigius, son of Emilius, Count of Laon, but eventually became a convert to Christianity, and accepted baptism at his hands. Secular history has celebrated the fight of Tolbiac—the invocation addressed by the despairing Frank to the God of the Christians; the sudden rallying of his fainting troops, and the last desperate charge which swept away for ever the power of the Alemanni as a nation. Saintly legends have enlarged upon the piety of Queen Clotilda; the ability of St. Remi; the pomp and ceremony which marked the baptism of Clovis at Reims in December 496; the memorable injunction of the bishop to his royal convert to adore the cross he had burnt, and burn the idols he had hitherto adored; and the miracle of the Sainte Ampoule, a vial of holy oil said to have been brought direct from heaven by a snow-white dove in honour of the occasion. A pigeon, however, has always been a favourite item in the conjuror’s paraphernalia from the days of Apolonius of Tyana and Mahomet down to those of Houdin and Dr. Lynn; and modern scepticism has suggested that the celestial regions were none other than the episcopal dovecot. Whether or not the oil was holy, we may be certain that the wine which flowed freely in honour of the Frankish monarch’s conversion was ambrosial; that the fierce warriors who had conquered at Soissons and Tolbiac wetted their long moustaches in the choicest growths that had ripened on the surrounding hills; and that the Counts and Leudes, and, judging from national habits, the King himself, got royally drunk upon a cuvée réservée from[Pg 5] the vineyard which St. Remi had planted with his own hands on his hereditary estate near Laon, or the one which the slave Melanius cultivated for him just without the walls of Reims.

For the saint was not only a converter of kings, but, what is of more moment to us, a cultivator of vineyards and an appreciator of their produce. Amongst the many miracles which monkish chroniclers have ascribed to him is one commemorated by a bas-relief on the north doorway of Reims Cathedral, representing him in the house of one of his relatives, named Celia, making the sign of the cross over an empty cask, which, as a matter of course, immediately became filled with wine. That St. Remi possessed such an ample stock of wine of his own as to have been under no necessity to repeat this miracle in the episcopal palace is evident from the will penned by him during his last illness in 530, as this shows his viticultural and other possessions to have been sufficiently extensive to have contented a bishop even of the most pluralistic proclivities.[8]

It is curious to note the connection between the spread of viticulture and that of Christianity—a connection apparently incongruous, and yet evident enough, when it is remembered that wine is necessary for the celebration of the most solemn sacrament of the Church. Christianity became the established religion of the Roman Empire about the first decade of the fourth century, and Paganism was prohibited by Theodosius at its close; and it is during this period that we find the culture of the grape spreading throughout Gaul, and St. Martin of Tours preaching the Gospel and planting a vineyard coevally. Chapters and religious houses especially applied themselves to the cultivation of the vine, and hence the origin of many famous vineyards, not only of the Champagne but of France. The old monkish architects, too, showed their appreciation of the vine by continually introducing sculptured festoons of vine-leaves, intermingled with massy [Pg 6]clusters of grapes, into the decorations of the churches built by them. The church of St. Remi, for instance, commenced in the middle of the seventh century, and touched up by succeeding builders till it has been compared to a school of progressive architecture, furnishes an example of this in the mouldings of its principal doorway; and Reims Cathedral offers several instances of a similar character.

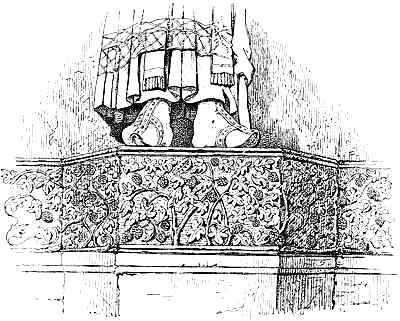

Amidst the anarchy and confusion which marked the feeble sway of the long-haired Merovingian kings, whom the warlike Franks were wont to hoist upon their bucklers when investing them with the sovereign power, we find France relapsing into a state of barbarism; and though the Salic law enacted severe penalties for pulling up a vine-stock, the prospect of being liable at any moment to a writ of ejectment, enforced by the aid of a battle-axe, must have gone far to damp spontaneous ardour as regards experimental viticulture. The tenants of the Church, in which category the bulk of the vine-growers of Reims and Epernay were to be classed, were best off; but neither the threats of bishops nor the vengeance of saints could restrain acts of sacrilege and pillage. During the latter half of the sixth century Reims, Epernay, and the surrounding district were ravaged several times by the contending armies of Austrasia and Neustria; and Chilperic of Soissons, on capturing the latter town in 562, put such heavy taxes on the vines and the serfs that in three years the inhabitants had deserted the country. Matters improved, however, during the more peaceful days of the ensuing century, which witnessed the foundation of numerous abbeys, including those of Epernay, Hautvillers, and Avenay; and the planting of fresh vineyards in the ecclesiastical domains by Bishop Romulfe and his successor St. Sonnace, the latter, who died in 637, bequeathing to the church of St. Remi a vineyard at Villers, and to the monastery of St. Pierre les Dames one situate at Germaine, in the Mountain of Reims.[9] The sculptured saint on the exterior of Reims Cathedral, with his feet resting upon a pedestal[Pg 7] wreathed with vine-leaves and bunches of grapes, may possibly have been intended for one of these numerous wine-growing prelates.

The mighty figure of Charlemagne, overshadowing the whole of Europe at the commencement of the ninth century, appears in connection with Reims, where, begirt with paladins and peers, he entertained the ill-used Pope Leo III. right royally during the ‘festes de Noel’ of 805. The monarch who is said to have clothed the steep heights of Rudesheim with vines was not indifferent to good wine; and the vintages of the Champagne doubtless mantled in the magic goblet of Huon de Bordeaux, and brimmed the horns which Roland, Oliver, Doolin de Mayence, Renaud of Montauban, and Ogier the Dane, drained before girding on their swords and starting on their deeds of high emprise—the slaughter of Saracens, the rescue of captive damsels, and the discomfiture of felon knights—told in the fables of Turpin and the ‘chansons de geste.’ That the cultivation of the grape, and above all the making of wine, had been steadily progressing, is clear from the fact that the distinction between the ‘Vins de la Rivière de Marne’ and the ‘Vins de la Montagne de Reims’ dates from the ninth century.[10]

This era is, moreover, marked by the inauguration of that long series of coronations which helped to spread the popularity of the Champagne wines throughout France by the agency of the nobles and prelates taking part in the ceremony. Sumptuous festivities marked the coronation of Charlemagne’s son Louis in 816; and the officiating Archbishop Ebbon may have helped to furnish the feast with some of the produce from the vineyard he had planted at Mont Ebbon, generally identified with the existing Montebon, near Mardeuil. It is of this vineyard that Pardulus, Bishop of Laon, speaks in a letter addressed by him to Ebbon’s successor, the virtuous Hincmar, who assumed the crozier in 845, proffering him counsels as to the best method of sustaining his failing health. After telling him to avoid eating fish on the same day that it is caught, insisting that salted meat is more wholesome than fresh, and recommending bacon and beans cooked in fat as an excellent digestive, he proceeds: ‘You must make use of a wine which is neither too strong nor too weak—prefer, to those produced on the summit of the mountain or the bottom of the valley, one that is grown on the slopes of the hills, as towards Epernay, at Mont Ebbon; towards Chaumuzy, at Rouvesy; towards Reims, at Mersy and Chaumery.’ The Champagne vineyards suffered grievously from the internal convulsions which marked the period when the sceptre of France was swayed by the feeble hands of the dregs of the Carlovingian race. The Normans, who threatened Reims and sacked Epernay in 882, swept over them like devouring locusts; and their annals during the following century are written in letters of blood and flame.

Times were indeed bad for the peaceful vine-dressers in the tenth century, when castles were springing up in every direction; when might made right, and the rule of the strong hand alone prevailed; and when the firm belief that the end of the world was to come in the year 1000 led men to live only for the present, and seek to get as much out of their fellow-creatures as they possibly could. Such natural calamities as that of 919, when the wine-crop entirely failed in the neighbourhood of Reims, were bad enough; but the continual incursions of the Hungarians, whose arrows struck down the peasant at the plough and the priest at the altar, and the memory of whose pitiless deeds yet survives in the term ‘ogre;’ the desperate contest waged for ten years by Heribert of Vermandois to secure the bishopric of Reims for his infant son, during which hardly a foot of the disputed territory remained unstained by blood; the repeated invasions of Otho of Germany; and the struggle between Hugh Capet and Charles of Lorraine for the titular crown of France,—left traces harder to be effaced. Reims underwent four sieges in about sixty years; and Epernay, that most hapless of towns, was sacked at least half a score of times, and twice burnt, one of the most conscientiously executed pillagings being that performed in 947 by Hugh the Great, who, as it was vintage-time, completely ravaged the whole country, and carried off all the wine.[11]

Under the rule of the Capetian race matters improved as regarded foreign foes, though the archbishops [Pg 8]had in the early part of the eleventh century to abandon Epernay, Vertus, Fismes, and their dependencies to the family of Robert of Vermandois, who had assumed the title of Counts of Champagne, to be held by them as fiefs. The fame of the schools of Reims, where future popes and embryo emperors met as class-mates; the festive gatherings which marked the coronation of Henry I. and Philip I.; the great ecclesiastical council held by Leo IX., which procured for the city the nickname of ‘little Rome;’ and the growing importance of the Champagne fairs, the great meeting-places throughout the Middle Ages of the merchants of Spain, Italy, and the Low Countries,—favoured the prosperity of the district and the production of its wine. Urban II., a native of Châtillon, who wore the triple crown from 1088 to the close of the century, was, prior to his elevation to the chair of St. Peter, a canon of Reims, under the name of Eudes or Odo, and, tippling there in company with his fellow-clerics, acquired a taste for the wine of Ay, which he preferred to all others in the world.[12] Pilgrims to Rome found penance light and pardon easily obtained when they bore with them across the Alps, in addition to staff and scrip, a huge ‘leathern bottel’ of that beloved vintage which warmed the pontiff’s heart and whetted his wit for the delivery of those soul-stirring orations at Placentia and Clermont, wherein he appealed to the chivalry of Western Europe to hasten to the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre from the hands of the infidel.

The result of these appeals was felt by the vine-cultivators of the Champagne in more ways than one, and their case recalls that of the petard-hoisted engineer. The virtuous, the speculative, and the enthusiastic who followed Peter the Hermit and Walter the Penniless to the plains of Asia Minor suffered at the hands of the vicious, the prudent, and the practical, who remained at home and passed their time in pillaging the estates of their absent neighbours. The abbatial vineyards suffered like the others; and the monks of St. Thierry, in making peace with Gerard de la Roche and Alberic Malet in 1138, complained bitterly of wine violently extorted during two years from growers on the ecclesiastical estate and of a levy made upon their vineyard.[13]

The efforts of Henry of France, a warlike prelate, who built fortresses and attacked those of the robber-nobles, and of Louis VII., who avenged the wrongs of the church of Reims on the Counts of Roucy, served to improve matters; and we may be sure that whenever the monks did get hold of a repentant or dying sinner, they made him pay pretty dearly for peace with them and Heaven. Colin Musset, the early Champenois poet, thought that the best use to which money could be put was to spend it in good wine.[14] Churchmen, however, managed to secure the desired commodity without any such outlay, for numerous charters of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries show lords, sick or about starting for the crusades, making large gifts to abbeys and monasteries; and many a strip of fair and fertile vineland was thus added, thanks to a judicious pressure on the conscience, to the already extensive possessions of the two great monasteries of Reims, St. Remi and St. Nicaise, and also to that of St. Thierry. The Templars, too, whose reputation as wine-bibbers was only inferior to that of the monks, if we may credit the adage which runs,

and who, prior to the catastrophe of 1313, had a commandery at Reims, possessed either vineyards, or droits de vinage, at numerous spots, including Epernay, Hermonville, Ludes, and Verzy; while the separate community of these ‘Red Monks’ installed at Orilly had estates at Ay, Damery, and Mareuil. The hospital of St. Mary at Reims also reckoned amongst its possessions vineyards at Moussy, bequeathed by Canon Pontius and Tebaldus Papelenticus. The wine, which in 1215 the treasurer of the chapter of Reims Cathedral obtained from that body an acknowledgment of his right to on the anniversaries of the deaths of Bishops Ebalus and Radulf, and that to which the sub-treasurer and carpenter were severally entitled, was no doubt in part derived from the vineyard planted in 1206 by Canon Giles at the Porte Mars and bequeathed by him to the chapter, and [Pg 9]the one which Canon John de Brie had purchased at Mareuil and had similarly bequeathed.[15] Although papal bulls and archiepiscopal warrants had forbidden the levying of the droit de vinage on wine vintaged by religious communities, in 1252 Pope Innocent IV. had to reprove the barons for interfering with the monastic vintages in the neighbourhood of Reims, and to threaten them with excommunication if they repeated their offence.[16]

These ecclesiastical topers, as a rule, were sufficiently critical of the quality of the liquor meted out to them, and an agreement respecting the dietary of the Abbey of St. Remi, at Reims, drawn up in 1218 between the Abbot Peter and a deputation of six monks representing the rest of the brethren, provides that the wine procured for the latter should be improved by two-thirds of the produce of the Clos de Marigny being set apart for their exclusive use. Ten years later, to put a stop to further complaints on the part of these worthy rivals of Rabelais’ Frère Jean des Entonnoirs, Abbot Peter was fain to agree that two hundred hogsheads of wine should be annually brought from Marigny to the abbey to quench the thirst of his droughty flock, and that if the spot in question failed to yield the required amount the deficiency should be made up from his own private and particular vineyards at Sacy, Villers-Aleran, Chigny, and Hermonville.[17]

We can readily picture these

or the cellarer quietly chuckling to himself as he loosened the spiggot of the choicest casks—

The monks were in the habit of throwing open their monasteries to all comers, under pretext of letting them taste the wine they had for sale, until, in 1233, an ecclesiastical council at Beziers prohibited this practice on account of the scandal it created. Petrarch has accused the popes of his day of persisting in staying at Avignon when they could have returned to Rome, simply on account of the goodness of the wines they found there. Some similar reasons may have led to the selection [Pg 10]of Reims, during the twelfth century, as a place for holding great ecclesiastical councils presided over by the sovereign pontiff in person; and no doubt ‘Bibimus papaliter’ was the motto of Calixtus, Innocent, and Eugenius when the labours of the day were done, and they and their cardinals could chorus, apropos of those of the morrow,

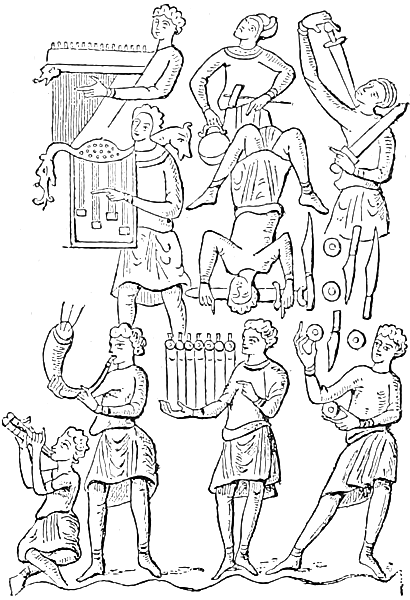

The kings of France may have preferred the wines of the Orleanais and the Isle of France, and the monarchs of England have been content to vary the vintages of their patrimony of Guienne with an occasional draught of Rhenish; but the wines of the river Marne certainly found favour at Troyes, where the Counts of Champagne, to whom Epernay had been ceded as a fief, held a court little inferior in state to that of a sovereign prince. The native vintage mantled in the goblets and beakers that graced the board where they sat at meat amidst their knights and barons, whilst minstrels sang and jongleurs tumbled and glee-maidens danced at the lower end of the hall. It fired the fancy of the poet Count Thibault, to whom tradition has ascribed the introduction of the Cyprus grape into France on his return from the Crusades,[18] and helped the flow of the amorous strains which he addressed to Blanche of Castille. Nor was he the only versifier of the time who could exclaim, with his compatriot Colin Musset, that ‘good wine caused him to sing and rejoice.’[19] Other local songsters, such as Doete de Troyes, Eustache le Noble, and Guillaume de Machault, sought inspiration at their native Helicon, and were equally ready with Colin Musset to appreciate a gift of

in return for their rhymes. It was this wine that the gigantic John Lord of Joinville, Seneschal of Champagne under Thibault, and chronicler of the Seventh Crusade, was in the habit of consuming warm and undiluted, by the advice of his physicians, on account, as he himself mentions, of his ‘large head and cold stomach;’ a practice which seems to have scandalised that pious and ascetic monarch St. Louis, who was careful to temper his own potations with water. The king was most likely not unacquainted with the wine, as a roll of the expenses incurred at his coronation at Reims, in 1226, shows that 991 livres were spent in wine on that occasion, when, in consequence of the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see, the crown was placed upon his head by Jacques de Bazoche, Bishop of Soissons.

Henry of Andelys, a compatriot of the engineer Brunel, who flourished, if a poet can be said to flourish, in the latter half of the thirteenth century, has extolled the wines of Epernay and [Pg 11]Hautvillers, and mentioned that of Reims, in his poem entitled the ‘Bataille des Vins.’ He informs us at the outset that ‘the great King Philip Augustus,’ whom state records prove to have had a score of vineyards in different parts of France,[21] was very fond of ‘good white wine.’ Anxious to make a choice of the best, he issued invitations to all the most renowned crûs, French and foreign, and forty-six different vintages responded to this appeal; amongst them Hautvillers and Epernay, described as ‘vin d’Auviler’ and ‘vin d’Espernai le Bacheler.’ The king’s chaplain, an English priest, makes a preliminary examination, resulting in the summary rejection of many competitors, till at length, as Argenteuil—‘clear as oil’—and Pierrefitte are disputing as to their respective merits, Epernay and Hautvillers simultaneously exclaim, ‘Argenteuil, thou wishest to degrade all the wines at this table. By God, thou playest too much the part of constable. We excel Châlons and Reims, remove gout from the loins, and support all kings.’[22] But lo, up jumps the ‘vin d’Ausois,’ the ‘Osey’ of so many of our English mediæval poets, with the reproach, ‘Epernay, thou art too disloyal; thou hast not the right of speaking in court;’[23] and enumerates the blessings which he and his demoiselle ‘la Mosele’ confer upon the Germans.[24] La Rochelle in turn reproves Ausois, and extols the strength of his own wines, and those of Angoulême, Bordeaux, Saintes, and Poitou, and boasts of the welcome accorded to them in the northern states of Europe, including England, to which the districts he mentions then belonged.[25]

The vintages of the then little kingdom of France put in a counter-claim for finesse and flavour as opposed to strength, and maintain that they do not harm those who drink them. The dispute becomes general, and the wines, heated with argument, exhale a perfume of ‘balsam and amber,’ till the hall where they are met resembles a terrestial paradise. The chaplain, after conscientiously tasting the whole of them, formally excommunicated with bell, book, and candle all the beer brewed in England and Flanders, and then went incontinently to bed, and slept for three days and three nights without intermission. The king thereupon made an examination himself, and named the wine of Cyprus pope, and that of Aquilat[26] cardinal, and created of the remainder three kings, five counts, and twelve peers, the names of which, unfortunately, have not been preserved.