JACK CADE—“There shall be in England seven halfpenny loaves sold for a penny, the three hooped pot shall have seven hoops, and I will make it felony to drink small beer.”—Hen. VI., Part II. Act iv. Scene 2.

ANCIENT AND CURIOUS LAWS RELATING TO THE MANUFACTURE AND SALE OF ALE AND BEER.

INGS, Parliaments and Local Authorities have, from very early times up to the present, more or less interfered with the production and sale of alcoholic liquors. As a rule, the laws and regulations made by them had the benevolent object of preserving the public health and pocket, but to modern notions they appear for the most part arbitrary and vexatious enactments which unduly oppressed an important industry.

INGS, Parliaments and Local Authorities have, from very early times up to the present, more or less interfered with the production and sale of alcoholic liquors. As a rule, the laws and regulations made by them had the benevolent object of preserving the public health and pocket, but to modern notions they appear for the most part arbitrary and vexatious enactments which unduly oppressed an important industry.

Before dealing with the many early references to laws concerning the brewing and sale of ale, it will be interesting to notice a few of the curious regulations to be found in the Canons of ancient religious orders enjoining sobriety on the members of their communities. Almost, if not quite, the earliest of the kind is attributed to St. Gildas the Wise, who lived towards the close of the sixth century, and is to the effect that, if any monk through drinking too freely gets thick of speech, so that he cannot join in the psalmody, he is to be deprived of his supper.

The Canons of St. David’s contain further rules on the same matter. Priests about to minister in the temple of God, and drinking wine or strong drink through negligence, and not ignorance, must do penance three days. If they have been warned, and despise, then forty days. Those who get drunk from ignorance must do penance fifteen days; if through negligence, forty days; if through contempt, three {97}quarantains. He who forces another to get drunk out of hospitality, must do penance as though he had got drunk himself. But he who out of hatred or wickedness, in order to disgrace or mock at others, forces them to get drunk, if he has not already sufficiently done penance, must do penance as a murderer of souls.

That these restrictions were not confined to clerics may be seen from the decree of Theodore, seventh Archbishop of Canterbury (A.D. 668–693), that if a Christian layman drink to excess, he must do a fifteen-days’ penance.

King Edgar seems to have gone nearer to the programme of the United Kingdom Alliance. Strutt says of him that under the guidance of Dunstan he put down many alehouses, suffering only one to exist in a village. He also ordered that pegs should be fastened in the drinking horns at intervals, that whosoever drank beyond these marks at one draught should be liable to punishment. We find, however, that this last-mentioned device defeated its own end, and became a provocative of drinking, so that in 1102, Anselm decreed, “Let no priest go to drinking bouts, nor drink to pegs (ad pinnas).” The custom was called pin-drinking or pin-nicking, and is the origin of the phrase, “He is in a merry pin,” and, doubtless, also of the expression, “Taking him down a peg.”

The peg-tankards, as they were called, contained two quarts, and were divided into eight draughts by means of these pegs; they passed from hand to hand, and each must drink it down one peg, no more, no less, under pain of fine.

In a code of Dunstan, for the regulation of the religious orders, were further injunctions to the priesthood, in which it was enjoined that no drinking be allowed in the Church, that men should be temperate at Church-wakes, that a priest should beware of drunkenness, and should in no wise be an ale-scop (i.e., a reciter at an ale-house). If we may believe the strange story of St. Dunstan, as recorded by the graphic pen of the author of the Ingoldsby Legends, we shall have little difficulty in accounting for the Saint’s abhorrence of strong drink. The legend is a good illustration of the maxim, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” Lay-brother Peter discovers that the Saint’s miraculous powers are due to his magical control over a broomstick, and that, on his uttering certain mystic words, the broomstick is compelled to do his bidding. Lay-brother Peter determines to apply his knowledge of the broomstick’s powers to his own temporal advantage. Having spoken the mystic words,{98}

Peter, full of his fun,Cries, “Broomstick! you lubberly son of a gun!Bring ale!—bring a flagon—a hogshead—a tun!’Tis the same thing to you; I have nothing to do;And, ’fore George, I’ll sit here, and I’ll drink till all’s blue.”

Alas! too literally the broomstick obeys the command; and the poor lay-brother, not having at command the spell that may compel the broomstick to desist, “after floating a while like a toast in a tankard,” is at last overwhelmed, and perishes in the brown flood he has so incautiously called up.

In vain did St. Dunstan exclaim, “Vade retroStrongbeerum! discede a Lay-fratre Petro!”

However, the impression made upon the good Saint’s mind was indelible, and has left its traces in the regulations made by him relating to drunkenness.

Elfric’s Canons, also, are directed towards putting down the custom of drinking in churches. They lay down that men ought not to drink and eat immoderately in churches, for “men often act so absurdly as to sit up by night, and drink to madness in God’s house.”

Some of the earliest laws directed against a particular custom in which ale figured as the principal beverage, were the prohibitions to be met with in the records of the 13th century with regard to what were called scot-ales. A scot-ale was a meeting for the purpose of consuming ale, and its name was derived from the fact that the drinkers divided40 the expenses of the entertainment amongst them. These feasts were forbidden in the reign of King John by Fitz-piers and Peter of Winchester, the regents of the kingdom, on the ground that they were made occasions for extortion. The forests, which then spread over great tracts of country, were not subject to the common law, but to the laws of the forest only, and we are told that the foresters and their minions not only set up ale-houses, but even compelled people living near to come in and join in scot-ales, for the sake of the revenue accruing therefrom. In 1256 Giles of Bridport, Bishop of Salisbury, {99}interdicted scot-ales, and commanded rectors, vicars, and other parish priests to exhort their parishioners that they violate not rashly the prohibition. In certain places the term scot-ale was used to denote one of the services paid by tenants to the lord or his bailiff on the periodical tour of inspection, and Bracton mentions that the Itinerant Justices were directed to inquire whether any viscounts or bailiffs brew their own ale, “which they call scot-ale or filct-ale,” for the purpose of extorting money from the tenants.

40 Cf. The modern expressions scot free and paying the shot.

Somewhat similar in practice, though distinct in origin and in the purpose of their institution, were the festivals called Bede-ales. These curious celebrations are described in Prynne’s Canterburie’s Doome (1646) as public meetings, “when an honest man decayed in his fortune is set up again by the liberal benevolence and contribution of friends at a feast; but this is laid aside at almost every place.” The custom somewhat reminds one of the saying that the British are wont to drink themselves out of debt, an allusion, of course, to the enormous revenue collected on malt and other liquors. We must suppose, however, that the practice of bede-ale was abused; the more generous and kindly-hearted a man might be, the more tipsy he would have to make himself in order to help his unfortunate “decayed” friend in the manner prescribed. Accordingly we find in ancient records prohibitions of this custom. One such may be cited from the records of the Borough of Newport, Isle of Wight: “Atte the Lawday holden here in the 8th day of October, the second yeare of the Reigne of King Edward the iiijth in the time of William Bokett and Henry Pryer, Bayliffs, Thomas Capford and William Spring, Constables, it is enacted furthermore that none hereafter, whether Burgesse or any other dweller or inhabitant, within this Towne aforesaid, shall make or procure to bee made, any Ale, commonly called Bede-Ale, within the liberty, nor within this Towne or without, upon payne of looseing xxd. to be payde to the Keeper of the Common Box.”

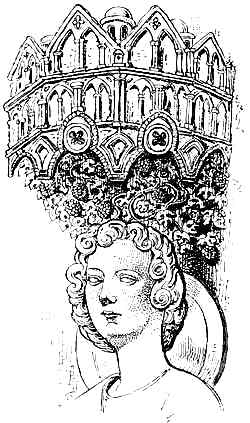

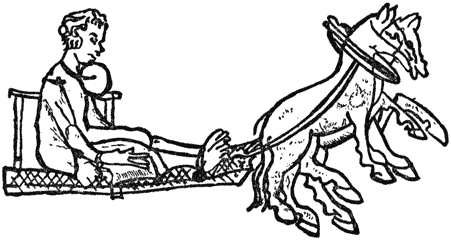

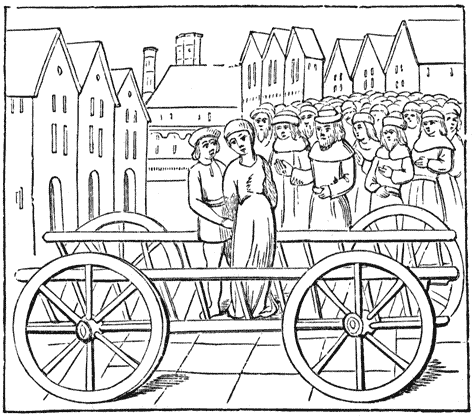

About the time of Henry III., we begin to find mention in the records of the period, of persistent attempts to fix the prices of bread and ale. Laws made with this end in view were termed collectively the Assisa Panis et Cervisiæ (i.e., The Assize of Bread and Ale). In the fifty-first year of that reign, we find it enacted that when a quarter of wheat is sold for iiis. or iiis. ivd., and a quarter of barley for xxd. or iis., and a quarter of oats for xvid., then brewers (braciatores) in cities ought, and may well afford, to sell two gallons of ale for a penny, and out of cities to sell three or four gallons for the same sum. By a statute {100}passed in the same year it is enacted that if a baker or a brewster41 (braciatrix) be convicted, because he or she hath not observed the Assise of Bread and Ale, the first, second, or third time, he or she shall be amerced according to the offence, if it be not over grievous; but if the offence be grievous and often, and will not be corrected, then he or she shall suffer corporal punishment, to wit, the Baker to the pillory, the brewster to the tumbrel (a cart for ignominious punishment), or to flogging. (The illustration represents a woman undergoing the punishment

The Tumbrel.

of the tumbrel, and is taken from the MS. Cent Nouvelles in the Hunterian Library.) A jury of six lawful men is to be summoned in every township, who are to be sworn faithfully to collect all measures of the town, to wit, bushels, half and quarter bushels, gallons, pottles and quarts, as well from taverns as from other places. The jurymen are to inquire how the assise of bread has been kept, and adjudge accordingly; they are then to inquire of the assise of Ale in the Court of the Town, what it is, and whether it has been observed; and if {101}not, they are to inquire what brewsters have sold contrary to the assises and they shall present their names distinctly and openly, and adjudge them to be fined or to the tumbrel.

41 The old word brewster is here used in its proper signification of a female brewer. The Brewster Sessions, as Licensing Sessions are called in many parts of the country, preserve the name, though the original feminine signification has disappeared. For an account of the early brewsters and ale-wives the reader is referred to Chapter VI.

By another statute, of rather uncertain date, but passed about this period, it is enacted that the standard of bushels, gallons, and ells (standardum busselli galonis et ulne) is to be marked with an Iron Seale of our Lord the King, and safe kept, under pain of £100, and no measure is to be used in any town unless it do agree with the King’s measure, and be marked with the seal of the shire town; and if any do sell or buy by measures unsealed, and not examined by the Mayor or Bailiffs, he shall be grievously amerced and all the measures of every Town, both great and small, shall be viewed and examined twice in the year; and if any be convict for a double measure, to wit, a greater for to buy with, and a lesser for to sell with, he shall be imprisoned for his falsehood (tanquam falsarius) and shall be grievously punished.

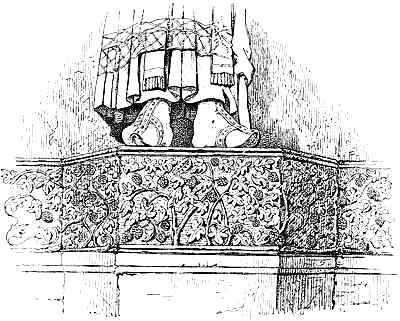

The Pillory.

The manner in which the various standard measures of capacity were arrived at is worthy of mention. It is enacted that: “One English penny, called a stirling, round and without any clipping, shall weigh twenty-two wheat corns in the midst of the ear, and twenty pence shall make an ounce, and twelve ounces a pound, and eight pounds shall make a gallon of wine, and eight gallons of wine shall make one bushel London, and eight bushels one quarter.”

We are glad to observe that a subsequent statute was passed which provided that both the pillory, or stretch-neck (collistrigium) as it was called, and also the tumbrel, must be of suitable strength, so that offenders might be punished without bodily peril.

The collistrigium given below is taken from an old drawing in the City Records, temp. Ed. III.

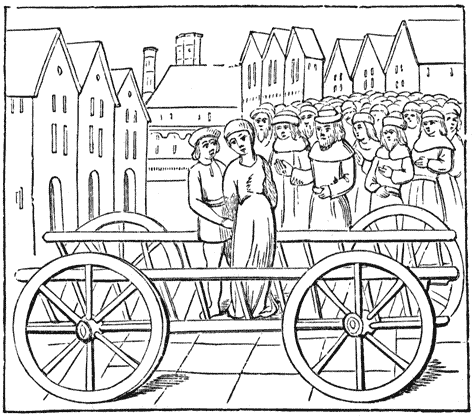

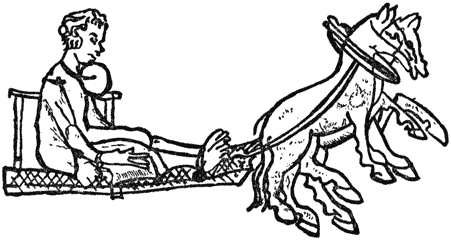

In the City of London the comparative severity of the punishments of the fraudulent baker and brewer seems to have been the reverse of that ordained by statute; the baker suffered the heavier penalty, being condemned to what was called the “judicium claye,” or condemnation to the hurdle, which, as described in the Liber Albus, was certainly a most unpleasant form of punishment. On conviction for selling short weight the defaulting baker was to be drawn upon a hurdle from the Guildhall to his own house, “through the great streets where there be most people {102}assembled, and through the great streets that are most dirty.” The illustration is taken from the Assissa Panis (temp. Edw. I.), preserved among the City Records. The defaulting brewer or brewster, in the reign of Edw. III., for the first offence was to forfeit the ale, for the second to forswear the mistier (the mystery or art of brewing), and on the third offence to forswear the City for ever. However, the

Punishment of the Hurdle.

penalties varied from time to time, for in the reign of Henry V., when the Liber Albus was compiled, the punishment of a brewster convicted of selling ale contrary to the assize was, that for the first offence she was to be fined 10s., for the second 20s., and for the third that she should suffer the “punishment provided for her in Westchepe,” which would probably be the tumbrel or the pillory. Some confusion as to the appropriate punishment occasionally arose. In 1257, Sir Hugh Bygot, as Grafton’s Chronicle tells us, “came to the Guylde-hall, and kept his Court and Plees there, without all order of law, and contrary to the libertyes of the citie, and there punished the bakers for lack of size by the tombrell, where beforetymes they were punished by the Pillorye.”

Offending brewers and bakers, in some places, suffered on the Cucking Stool. In the Borrow Lawes of Scotland, speaking of Browsters (“Wemen quha brewes aill to be sauld,”) it is said, “Gif she makes gude ail, that is sufficient. Bot gif she makes euel ail, contrair to the use and consuetude of the burg, and is convict thereof, she sall pay ane unlaw of aucht shillinges, or sal suffer the justice of the brugh, that is, she sall be put upon the Cock- stule, and the aill sall be distributed to the pure folke.”

In April, 1745, an ale-wife of Kingston-on-Thames was ducked in the river, for scolding, in the presence of two thousand or more people.

The following extracts from the old Assembly Books of Great {103}Yarmouth give some idea of the powers possessed by corporate bodies for the regulation of trade in olden times:―

“Friday before Palm Sunday, 7 Edwd. VI. Agreed that no inhabitant shall buy any beer to sell again but such as was brewed in the town, under pain of 6s. 8d. a barrel.

“Feb. 14. 1 Philip and Mary, 1554. M. Swansey, of Hickling, being a foreigner, bought of a merchant stranger certain hopps—the buyer to forfeit the Hopps, and he may buy them again of the Chamberlain.

“March 19. 1 Mary, 1554. No inhabitant shall buy nor no ship shall receive any beer brewed out of the town, under a penalty of 3s. 4d. per gallon.

“July 2. 1 Philip and Mary, 1554. No baker or brewer to bake or brewe in the town unless appointed by the bailiffs.

“Apl. 8. 15 Eliz., 1573. That brewers be ordered to brew with coals instead of wood, from the latter’s exhorbitant price.”

The Articles of the Free Fair (1658) held at Great Yarmouth, contain the following regulation:―

“Also that no brewer selle nor doe to be solde, a gallon of the beste ale above two pence: a gallon of the second ale above one pennye uppon the payne and perrille above sayde.”

The records of the old municipal corporations of England that have survived the destroying hand of time are very few, but it can hardly be doubted that they contained very similar regulations to those given above. In the Domesday Book of Ipswich an order of the reign of Edward I. provides as to Brewsters, that “after Michelmesse moneth, whan men may have barlych of newe greyn, the ballyves of the forseid toun doo cryen assize of ale by all the toun, after that the sellyng of the corn be. And gif ther be founden ony that selle or brewe a geyns the assise and the crye, be he punysshed be the forseyed ballyves and by the court for the trespas, after the form conteyned in the Statute of merchaundise (13 Edw. I., s. 3) of oure lord the kyng, and after law and usage of the same toun.”

Ricart’s Kalendar of the City of Bristol contains the following record: “Item, hit hath be usid, in semblable wyse, the seid maire anon aftir Mighelmas, to do calle byfore theym in the seide Counseill hous, all the Brewers of Bristowe; and yf the case require that malt be scant and dere, then to commen there for the reformacion of the same, and to bryng malte to a lower price, and that such price as shall be sette by the maier upon malte, that no brewer breke it, upon payne of XLs. forfeitable {104}to the Chambre of the Toune. And the shyftyng42 daies of the woke, specially the Wensdaies and Satirdaies, the mair hath be used to walke in the morenynges to the Brewers howses, to oversee thym in servyng of theire ale to the pouere commens of the toune, and that they have theire trewe mesures; and his Ale-konner with hym to taste and undirstand that the ale be gode, able, and sety keeping their sise, or to be punyshed for the same, aftir the constitucion of the Toune.”

42 The days when the ale was being moved to customers’ houses.

Sometimes a whole township was fined for the default of some of its members. In 1275 the township of Dunstable was fined 40s., because the brewers had not kept the assize.

Some curious and amusing entries are to be found in the Munimenta Academica of the University of Oxford, as to the regulations for the brewing trade in the fifteenth century. In the year 1434 we find it recorded that, “Seeing how great evils arise both to the clerks and to the townsmen of the City of Oxford, owing to the negligence and dishonesty of the brewers of ale,” Christopher Knollys, commissary, assembles the brewers together in the church of the Blessed Mary the Virgin, and commands them to provide sufficient malt for brewing; and that two or three shall twice or thrice in the week carry round their ale for public sale, under a penalty of 40s.; and John Weskew and Nicholas Core, two of their number, are appointed supervisors of the brewers. Each brewer is then made to swear on the Blessed Evangelists to brew good ale and wholesome, and according to the assize, “so far as his ability and human frailty permits.”

It would appear that very considerable disorders prevailed in that ancient seat of learning at this period. The Warden of Canterbury College, for instance, is accused of having incited his scholars to make a raid upon the ale of other scholars of the town, which they accordingly did, and carried off ale to the value of 12d.

The fair brewsters of the period seem to have held much the same ideas as to the relative importance of the patronage of Town and Gown as a fashionable Oxford tailor of the present day may be supposed to entertain. In 1439 Alice Everarde is suspended “ab arte pandoxandi” (from practising brewing) for ever, because she refused to brew ale for sale for the common people of Oxford.

In 1444 the brewers were made to swear before the Chancellor that they would brew wholesome ale, and in such manner that the water {105}should boil until it emitted a froth, that they would skim the froth away, and that they would give the ale sufficient time to settle before they sold it in the University; and Richard Benet swore that he would let his ale stand twelve hours to clear, before he carried it to hall or college, and that he would not mix the dregs with the ale when he carried it for sale within the University.

In 1449 the stewards and manciples of the college swear that nine of the brewers have broken the assize and have brewed “an ale of little or no strength, to the grave and no mean damage of the University and Town, and that they are obstinate and rebels and refuse to serve the Principals and others of the Halls with ale.” In 1464 John Janyn is ordered by the Commissary to refund to Anisia Barbour, without the east gate of Oxford, the sum of 8d., because he had sold her a cask of ale for 20d., and “in our opinion and that of others who have just tasted it, it is not worth more than 12d.”

The sister University exercised a similar jurisdiction over the brewing trade, and it is mentioned in Rymer’s Fœdera (R. 2. 934) that in the year 1336, on a petition of the Chancellor and scholars of the University of Cambridge, the ancient privilege of the University, that, on the demand of the Chancellor, the Mayor and bailiffs should make trial or assize of the bread or ale, was restored. A curious survival of the municipal jurisdiction over the vendors of Cambridge ale is recorded in Hone’s Every-Day Book, as existing at the annual fair on Stourbridge Common during the latter half of last century: “Besides the eight servants called red coats, who are employed as constables attendant upon the Mayor of Cambridge, who held a court of justice during the fair, there was another person dressed in similar clothing, with a string over his shoulders, from whence were suspended spigots and fossets, and also round each arm many more were fastened. He was called Lord of the Tap, and his duty consisted in visiting all the booths in which ale was sold, to determine whether it was a fit and proper beverage for the persons attending the fair.”

In making the ale of Old England, wheat was frequently malted and used with barley malt. In times of scarcity this practice was now and again forbidden as tending to unduly enhance the price of bread. In 1316, ground malt having risen during the preceding fourteen years from 3s. 4d. to 13s. 4d. the quarter, a proclamation was issued prohibiting the malting of wheat. The regulation, however, was unpopular and difficult to enforce, and wheat continued to be malted and mixed with the more appropriate grain. Receipts of more recent times frequently {106}mention this use of wheat malt. One of these of the sixteenth century is as follows:―

“To brewe beer. 10 quarters of malte, 2 quarters of wheete, 2 quarters of oates, 40 pound weight of hoppys—to make 60 barellys of sengyll beer; the barel of aell contains 32 galones, and the barell of beer 36 gallons.”

The restrictive legislation was not confined to ale, for in 1330 we find it enacted: “Because there are more taverners in the realm than were wont to be, selling as well corrupt wines as wholesome, and have sold the gallon at such price as they themselves would, because there was no punishment ordained for them, as hath been for them that sell bread and ale, to the great hurt of the people,” therefore wine must be sold at a reasonable price. No sum, however, appears to have been fixed, and we can well imagine that the ideas of the innkeeper and his customer might not altogether agree on the question of what was a reasonable price.

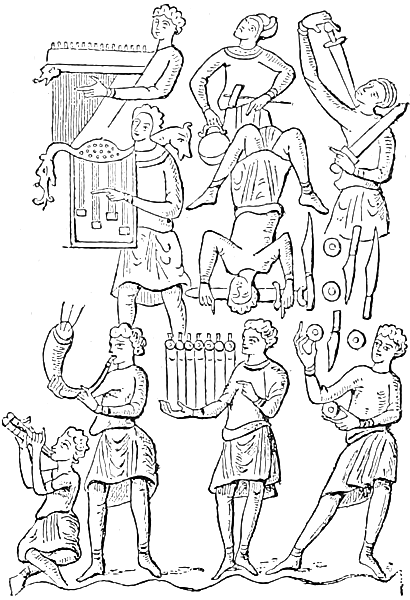

Not only was the price of ale fixed, but its strength and quality were also subjected to the experienced taste of the ale-conner, an officer appointed to test the goodness of the brew. The ale-conner’s appellation appears to be derived from his power of conning, i.e., knowing of or judging the liquor, and reminds one of Chaucer’s line:―

“Well coude he knowe a draught of London ale.”

The ale-conners were appointed annually in the courts leet of every manor; also in boroughs and towns corporate; and in many places, in compliance with charters and ancient custom, appointments to this office are still made, though the duties have fallen into disuse.

The following is the oath of this ale official, taken from the Liber Albus, compiled in the reign of Henry V. by John Carpenter, clerk, and Richard Whittington, mayor:—“You shall swear, that you shall know of no brewer, or brewster, cook, or pie-baker, in your ward, who sells the gallon of best ale for more than one penny halfpenny, or the gallon of second for more than one penny, or otherwise than by measure sealed and full of clear ale; or who brews less than he used to do before this cry, by reason hereof, or withdraws himself from following his trade the rather by reason of this cry; or if any persons shall do contrary to any one of these points, you shall certify the Alderman of your ward and of their names. And that you, so soon as you shall be required to taste any ale of a brewer or brewster, shall be ready to do the same; and in case that it be less good than it used to be before this cry, you, by assent {107}of your Alderman, shall set a reasonable price thereon, according to your discretion; and if any one shall afterwards sell the same above the said price, unto your Alderman you shall certify the same. And that for gift, promise, knowledge, hate or other cause whatsoever, no brewer, brewster, huckster, cook, or pie-baker, who acts against any one of the points aforesaid, you shall conceal, spare or tortuously aggrieve; nor when you are required to taste ale, shall absent yourself without reasonable cause and true; but all things which unto your office pertains to do, you shall well and lawfully do. So God you help, and the saints.” No doubt this oath was regularly repeated with due solemnity, but we can imagine with what a subtle irony the official described in The Cobler of Canterburie would have repeated the part of the oath having reference to absenting himself when required to taste ale.

A nose he had that gan show,What liquor he loved I trow;For he had before long seven yeare,Beene of the towne the ale-conner.

Absent himself—not if he knew it!

The ale-conners also had the power of presenting, i.e., accusing at the court leet, any brewer who refused to sell ale to his neighbours though he had some for sale.

The officials who tested ale bore various appellations. At the Court Leet of the Manor of New Buckenham, in Norfolk, the name under which this person was known was the ale-founder. In rolls of the same Manor of earlier date he is called Gustator Cervisiæ. In the records of the Manor Court of Hale in the 15th century, in a list of persons fined, occurs the entry, “Thomas Layet, quia pandocavit semel iid., et quia concelavit le fowndynge pot iiid.;” that is, a fine of 2d. was inflicted because he brewed in some manner contrary to the custom of the manor; as by not putting out his sign when he brewed, or by not summoning the ale-founder to taste the brew as soon as he had finished; and a fine of 3d. because he concealed the “fowndynge” pot, the vessel, probably, in which he had brewed.

In Scrope’s History of Castle Coombe we are told that the rules of that place in reference to the making and sale of ale were numerous and perplexing. No one was permitted to brew ale so long as any church-ale lasted, nor so long as the keeper of the park had any to sell, nor at {108}any time without licence of the lord or court; nor to sell without a sign, or, during the fair, without an ale-stake hung out, nor to ask a higher price for ale than that fixed by the jury of assize, nor to lower the quality below what the ale-tasters approved, nor to sell at times of Divine service, nor after nine o’clock at night, nor to sell at all without entering into a bond for £10, with a surety of £5, to keep orderly houses. The frequent changes in the price allowed show the difficulty the authorities had in settling the problem, how to have good liquor cheap. In the reign of Elizabeth all systematic attempts to set the price of ale seem to have been discontinued. At a court held in May in the tenth year of that queen, the tithing-man reported that “the ale-wyves had broken all the orders of the last laweday.” The court received the announcement in silence, and made no order. The ale-wives had conquered; let us hope they used their victory with discretion.

The practice seems to have prevailed here as elsewhere of compelling a brewer to put out his sign or ale-stake when he had brewed, as a signal to the local ale-conner that his services were required. In 1402 we find that John Lautroppe was presented to the court “quia brasiavit iij vicibus sub uno signo,” i.e., he had brewed three times but had only displayed the legal signal once. The only penalties recorded as being imposed for drunkenness appear to be one in 1618 and one in 1631; but it would hardly be safe to argue that the inhabitants of the district were an exceptionally sober race, for though the manor rolls of Castle Coombe date from 1346, no legislative effort to restrain excess in drinking was made till the reign of James I., and such laws were always highly unpopular, and were very sparingly or not at all enforced.

Tierney, in his History of Sussex, gives the following extract from the rolls of Arundel: “John Barbs, Roger Shadyngden, and others, brewers, refuse to sell a gallon of ale for one farthing according to the proclamation of the mayor, and are consequently fined twopence each.” The passage in the Taming of the Shrew, in which the servant, seeking to convince Christopher Sly that his former life is nothing but the delusion of a crazy brain, tells him how he would

. . . rail upon the mistress of the house,And say you would present her at the leet,Because she brought stone jugs and no sealed quarts,

shows that this jurisdiction of the manor courts was still in full force in Shakspere’s day.{109}

Kitchen, in his work on Courts (1663), in writing of courts leet, says:—“Also if tapsters sell by cups and dishes, or measures, sealed or unsealed, is enquirable.” It is noted in Dr. Langbaine’s collections, under January 23, 1617, that John Shurle had a patent from Arthur Lake, Bishop of Bath and Wells and Vice-Chancellor of Oxford, for the office of ale-taster (to the University). The office required “that he go to every ale-brewer that day they brew, according to their courses, and taste their ale; for which his ancient fee is one gallon of strong ale, and two gallons of less strong worth a penny.”

In some places the office of ale-conner still survives. The appointment of four ale-conners for the City of London is said to date as far back as the first charter of William the Conqueror. Originally they were elected by the folkesmote, afterwards at the wardmote, and from the time of Henry V. till the present day by the livery. We have before us an extract from a daily paper of the 16th September, 1884, in which is recorded the appointment of an ale-taster for the ancient borough of Christchurch.

The following curious application was made in the year 1864 to the manorial court of the Duke of Buccleuch:—“To the Manorial Court of the Right Hon. Walter Francis, Duke of Buccleuch and Queensbury, sitting at Haslingden, this 18th day of October, 1864.—This is to give notice to your honourable court, that I, Richard Taylor, by appointment for the last five years Ale-taster for that part of her Majesty’s dominions called Rossendale, do hereby tender my resignation to hold that office after this day, as I am wishful, while young and active, and as my talents are required in another sphere of usefulness, to devote them to that purpose. For five successive years your honourable court has done me the honour of electing me to the above office, which I have held, and performed the duties thereof efficiently, and without disgrace. Having won your confidence by holding this office, at a late sitting of your honourable court it pleased you to appoint me bellman for Bacup, and while I resign the former office, am wishful to hold my connexion with his Grace the Duke Francis Walter, to continue to cry aloud as bellman for Bacup, and, as heretofore, to cry for nothing for those who have nothing to pay with. Given under our hand and seal this 18th day of October, in the year of our Lord 1864. Signed, Richard Taylor, Ale-taster for Rossendale. God save the Queen.”

As early as the days of Edward I. attempts were made to bring about the early closing of taverns; but the authorities seem to have moved rather in the interests of peace than of temperance.{110}

In a preamble to a statute passed in that reign it is stated that “offenders, going about during the night, do commonly resort and have their meetings and evil talk in taverns more than elsewhere, lying in wait and watching their time to do mischief.” It is therefore enacted that taverns are to be closed at the tolling of the curfew bell. And if any taverner does otherwise, he shall be put on his surety, the first time by the hanap (a two-handled tankard, sometimes of silver) of his tavern, or by some other good pledge therein found, and fined 40d., with various cumulative punishments for successive offences until on the fifth conviction he shall forswear such trade in the City for ever.

In the year 1455 it was enacted “that no person that in the County of Kent shall commonly brew any ale or beer to sell, shall make nor do to be made any malt in his house, or in any other place to his own use, at his costs and expences above an C quarters in the year, under penalty of x li., and this statute is to be in force for the space of 5 years.” This act appears to have been passed to protect the maltsters of other places from the competition of the Kentish men. An act was passed in 1496 “against vacabonds and beggars,” which directs two justices of the peace to “rejecte and put away comen ale-selling in townes and places where they shall think convenyent, and to take suertie of the keepers of ale-houses of their gode behavyng, by the discrecion of the seid justices, and in the same to be avysed and aggreed at the time of their sessions.”

In 1531 brewers were forbidden to take more than such prices and rates as should be thought sufficient, at the discretion of the justices of the peace within every shire, or by the mayor and sheriffs in a city.

By 5 and 6 Edward VI. c. 25, entitled “An Act for Keepers of Ale-houses to be bounde by Recognizances,” it is enacted that “forasmuch as intolerable hurts and troubles to the commonwealth do daily grow and increase through such abuses and disorders as are had and used in common ale-houses, the Justices of the Peace are authorized to close such houses at their discretion.” And we find later, in Elizabeth’s time, that Lord Keeper Egerton, in his charge to the judges when going on circuit, bade them ascertain, for the Queen’s information, how many ale-houses the justices of the peace had pulled down, so that the good justices might be rewarded and the evil removed. Surely the advocates for total suppression of the sale of alcoholic drinks were born some two or three centuries too late! A quaint jingle, entitled “Skelton’s Ghost,” which may be attributed to some post-Elizabethan rhymer, contains an allusion to the legal price of ale.{111}

To all tapsters and tiplers,And all ale-house vitlers,Inne-keepers and cookes,That for pot-sale lookes,And will not give measure,But at your owne pleasure,Contrary to law,Scant measure will drawIn pot and in canne,To cozen a manOf his full quart a penny,Of you there’s too many.For in King Harry’s time,When I made this rimeOf Elynor Rumming,With her good ale tunning,Our pots were full quarted,We were not thus thwartedWith froth canne and neck potAnd such nimble quick shot,That a dowzen will scoreFor twelve pints and no more.

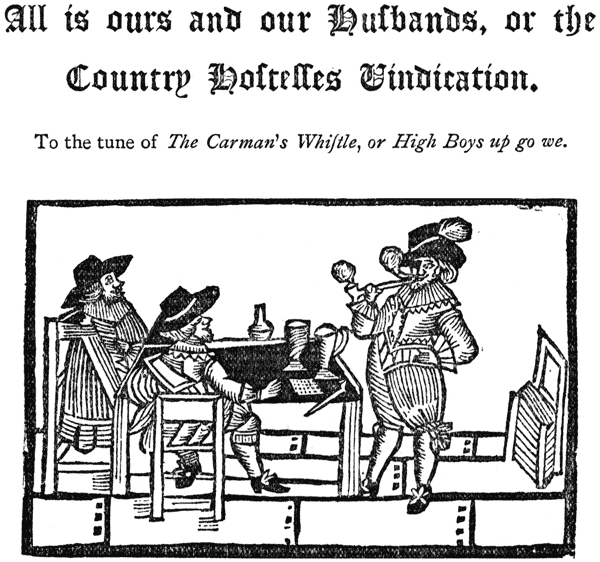

The views of a cozening hostess of the period are amusingly set forth in a quaint old ballad taken from the Roxburghe collection, a portion of which finds place on the following page.

The varying prices and qualities of ale and beer, as sanctioned by legal authority, have been so fully treated of in another part of this work (Chapter VIII.) that it is not necessary to dwell further upon the subject.

For if any honeſt companyOf boon good fellows come,And call for liquor merrilyIn any private room,Then I fill the Jugs with Froth,Or cheat them of one or two,If I can ſwear them out of bothThe reckoning is my due.

Roxburghe Ballads.

In the year 1531, brewers were forbidden to make the barrels in which their ale was sold. The reason for this extraordinary prohibition is thus given in the quaint words of the preamble of the act:—“Whereas the ale-brewers and beer-brewers of this realm of England have used, and daily do use, for their own singular lucre, profit, and gain, to make in their own houses their barrels, kilderkins, and firkins, of much less quantity than they ought to be, to the great hurt, prejudice, and damage of the King’s liege people, and contrary to divers acts, statutes, ancient laws and customs heretofore made, had, and used, and to the destruction of the poor craft and mystery of coopers,” therefore no beer-brewer or {113}ale-brewer is to “occupy . . . the mystery or craft of coopers.” The coopers are commanded to make every barrel, which is intended to contain beer for sale, of the capacity of xxxvi. gallons; ale barrels, however, are to contain but xxxii. gallons, and so in proportion for smaller vessels. The wardens of the coopers are empowered to search for illegal vessels, and to mark every correct vessel with “the sign and token of St. Anthony’s cross.” This cross is possibly the origin of the X, double X and treble X now in use upon casks. A correspondent of Notes and Queries, however, thinks that the letter X on brewers’ casks is probably thus derived:—Simplex—single X or X. Duplex—double X or XX. Triplex—treble X or XXX. This was suggested by Owen’s epigram, lib. xii. 34.

Laudatur vinum simplex, cerevisia duplexEst bona duplicitas, optima simplicitas.

From early times laws concerning our exports and imports were considered as specially appertaining to the royal prerogative. Corn and malt, ale and beer, could only be exported by royal licence. This is instanced by the order of Edward III., in 1366, to the ports of London, Sandwich, Bristol, Southampton, and eight other places:―

“The King, to the collectors of customs in the port of London, Greeting.

“We command you, that all merchants and others, who wish to export corn, malt, ale, and other victuals, be allowed, after first taking an oath or some other sufficient security from them, to export such things to our town of Calais and to other of our possessions, but not elsewhere.”

In later times a considerable revenue was raised for the Crown by the profits of these export licences. In the reign of Edward VI. the export of beer was regulated by an act (1543) which provides that no larger vessel than a barrel was to be used for export purposes, under fine of 6s. 8d., and that every exporter should give security for importing so much “clapboard” as would be an equivalent for the barrels he took out of the country. Queen Elizabeth jealously guarded the prerogative in this matter, and in her thrifty way seems to have made a pretty penny from the licences. English beer had at that time become widely famed, and could be obtained in foreign parts, as may be learnt by a letter from Charles Paget to Walsingham (1582), in which he announces that he is going to Rouen for his health, and intends to drink English beer.{114}

In 1572, Thomas Cantata, a Venetian, sought permission to export 200 tuns of beer, on condition of his making known to her Majesty certain inventions useful for the defence of the realm. In the same year one Th. Smith had licence to export 4,000 tuns of beer.

In 1586, Th. Cullen, of Maldon, Essex, applies to the Council by letter in which he asks, as a recompense for having discovered Mr. Mantell, a traitor, that he may have a licence as a free victualler for twenty-one years, or a licence to transport 400 tuns of beer, or else to have £40 in money. Even noblemen engaged in the export trade, for in 1603, licence was granted to Lord Aubigny to export 6,000 tuns of double beer.

The power of granting licences to inns and ale-houses in the days of Elizabeth and her immediate successors, was frequently given by letters patent to favourites or to persons prepared to pay for the privilege. In 1590 Wm. Carr received a licence for seven years, to give leave to any persons in London and Westminster to brew beer for sale. The abuses that grew out of this system formed one of the grievances examined into by Parliament in 1621.

A statute was passed in the fourth year of James I. enacting that “whereas the loathsome and odious sin of drunkenness is of late grown into common use, being the root and foundation of many other enormous sins, as bloodshed, etc., to the great dishonour of God and of our nation, the overthrow of many good arts, and manual trades, the disabling of divers good workmen, and the general impoverishment of many good subjects, abusively wasting the good creatures of God,” a fine of five shillings is imposed for drunkenness, together with six hours in the stocks. Some attempt had been previously made at legislation in this direction. In Townsend’s Historical Collections (1680) an account is found under date Tuesday, November 3rd, 1601, of a debate on a Bill to restrain the Excess and Abuse used in Victualling Houses. Mr. Johnson moved, that “bodily punishment might be inflicted on Alehouse keepers that should be offenders, and that provision be made to restrain Resort to Alehouses.” In the same bill Sir George Moore spoke against drunkenness, and desired “some special provision should be made against it;” and, “touching the Authority of Justices of the Assize and of the Peace, given by this bill, That they shall assign Inns, and Inn Keepers. I think that inconvenient: for an Inn is a man’s inheritance, and they are set at great rates, and therefore, not to be taken away from any particular man.” The attempt of James who, to tell the truth, was himself not by any means free from “the loathsome and hideous sin,” to {115}make his subjects sober by compulsion, seems to have met with but poor success, for in 1609 another statute was passed which, while confessing that, “notwithstanding all former laws and provisions already made, the inordinate and extreme vice of excessive drinking and drunkenness doth more and more abound,” enacts that a person convicted under the former act shall be deprived of his licence for the space of three years. In 1627 a fine of twenty shillings and a whipping is imposed for keeping an ale-house without a licence.

Drunkenness seems to have been prosecuted with some severity during the Commonwealth time, and the entries in the records of convictions for being “drunk in my view” would seem to point to the fact that the offenders were haled before the judgment seat ere the effects of their debauches had passed away.

As early as the middle of the fifteenth century some attempts were made to bring about “Sunday closing.” They seem to have taken the form, for the most part, of bye-laws of corporations, and to have been generally unsuccessful. In 1428 the corporation of Hull prohibited the vintners and ale-house keepers from delivering or selling ale upon the Sunday, under penalty of 6s. 8d. for sellers and 3s. 4d. for buyers. In 1444 an act was made by the Common Council of London “that upon the Sunday should no manner of thing within the franchise of the City be bought or sold, neither victual nor other things.” The attempt was apparently unsuccessful, as we are told that “it held but a while,” but it was renewed from time to time in some form or other. In 1555 an order was made by the Privy Council of Queen Mary, and directed to the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London, whereby taverns, ale or beer houses, &c., are directed to be closed on “Sondaye, or other festeyvall or hollye daye duringe all the severall tymes of mattyns, highe masse, and evynsonge, or of eny sermon to be songe or sayde within their severall parishe Churches upon payne of ymprysonmente, as well of the boddyes of every suche howseholder, as also of the boddyes of every suche persone as shall so presume to eate or drynke.” A hundred years later many entries occur in parish and other records of penalties for Sunday drinking.

The books of St. Giles’ parish furnish the following extracts:―

| 1641. | Received of the Vintner at the Catt in Queene Streete, for p’mitting of tipling on the Lord’s day | £1 | 10 | 0 |

| 1644. | Received of three poor men, for drinking on the Sabbath daie at Tottenham Court | £0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1646. | Received of Mr. Hooker, for brewing on a Fast day | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| 1648. | Received from Isabel Johnson, at the Cole Yard, for drinking on the sabbath day | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1655. | Received of a Mayd taken in Mrs. Jackson’s Ale-house on the sabbath day | 0 | 5 | 0 |

Received of a Scotchman drinking at Robert Owen’s on the Sabbath | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1658. | Received of Joseph Piers, for refusing to open his doores to have his house searched on the Lord’s daie | 0 | 10 | 0 |

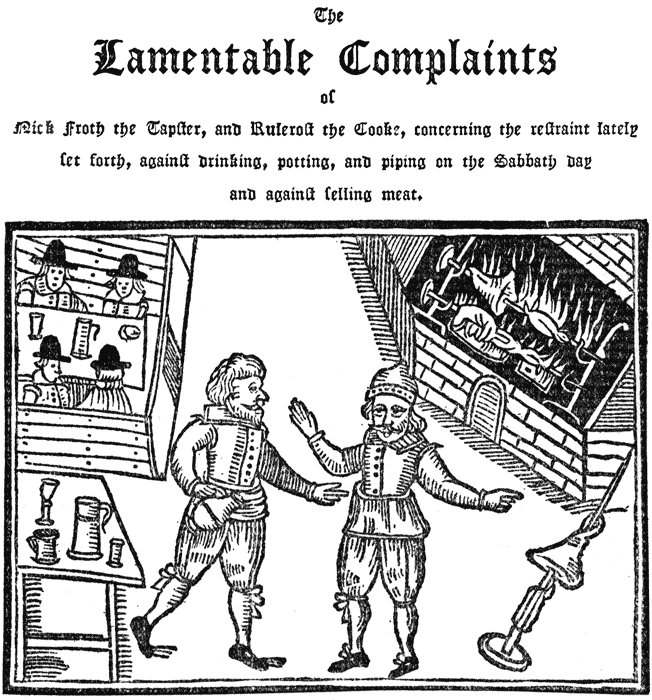

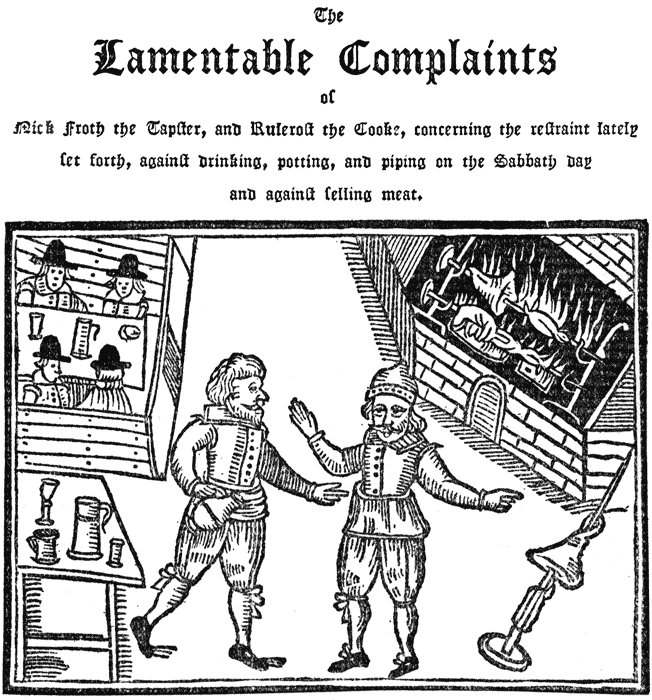

In 1641, an amusing pamphlet was published on the subject of Sunday closing. Its title, frontispiece, and an extract from its contents are given on the opposite page.

About this period was in vogue that curious old form of punishment which was known as the drunkard’s, or Newcastle, cloak. This garment was nothing more nor less than a beer barrel, worn in the manner shown in the accompanying illustration. Possibly the inventor of sandwich men derived his idea from this source.

Locke, in his second letter on Toleration, informs us that the intolerance of the age with regard to Dissent was carried to such length that hardly any walk in life was free from obstacles thrown in the way of Dissenters pursuing it. Amongst other things he mentions that those who had licences to sell ale were compelled to receive the Sacrament according to the rites of the Church of England. We are unable to find in contemporary records any confirmation of this alleged regulation.

Cook.—“There is ſuch news in the world will anger thee to heare of, it is as bad, as bad may be.”

Froth.—“Is there ſo? I pray thee what is it, tell me whatever it be.”

Cook.—“Have you not heard of the reſtraint lately come out againſt us, from the higher powers; whereby we are commanded not to ſell meat nor draw drink upon Sundays, as will anſwer the contrary at our perils.”

Froth.—“I much wonder, Maſter Ruleroſt, why my trade ſhould be put downe, it being ſo neceſſary in a Commonwealth.”

Efforts were made by the brewers from time to time to bring about an alteration in the law restricting the quality of beer to two sorts, the strong and the small. The Brewers’ Plea or a Vindication of Strong Beer, London, 1647, thus gives the views of the brewers on the advantages to be obtained by allowing stronger beer to be brewed:—“For of hops and malt, our native commodities (and therefore the more agreeable to the constitutions of our native inhabitants), may be made such strong beer (being well boiled and hopped, and kept its full time) as that {118}it may serve instead of Sack, if authority shall think fit, whereby they may also know experimentally the virtue of those creatures, at their full height; which beer being well brewed, of a low, pure amber colour, clear and sparkling, noblemen and the gentry may be pleased to have English Sack in their wine cellars, and taverns also to sell to those who are not willing, or cannot conveniently lay it in their own houses; which may be a means greatly to increase and improve the tillage of England, and also the profitable plantations of hop grounds . . . and produce at lesser rates (than wines imported) such good strong beer as shall be most cherishing to poor labouring people, without which they cannot well subsist; their food being for the most part of such things as afford little or bad nourishment, nay, sometimes dangerous; and would infect them with many sicknesses and diseases, were they not preserved (as with an antidote) with good beer, whose virtues and effectual operations, by help of the hop well boiled in it, are more powerful to expel poisonous infections than is yet publicly known, or taken notice of.”

Another ineffectual plea, somewhat later in date, may be here mentioned. In The grand concern of England explained in several proposals to the consideration of the Parliament, London, 1673, petition is made to Parliament that legislation of a protective nature may be granted to the brewers’ trade. The proposal is “That Brandy, Coffee, Mum, Tea, and Chocolate may be prohibited,” for these greatly hinder the consumption of Barley, Malt, and Wheat, the product of our land.

“But the prohibition of Brandy would be otherwise advantageous to the Kingdom, and prevent the destruction of his majesty’s subjects; many of whom have been killed by drinking thereof, it not agreeing with their constitutions.

“Before brandy (which is now become common and sold in every little alehouse) came over into England in such quantities as it now doth, we drank good strong beer and ale; and all laborious people (which are far the greatest part of the Kingdom), their bodies requiring, after hard labour, some strong drink to refresh them, did therefore every morning and evening use to drink a pot of ale, or a flagon of strong beer; which greatly promoted the consumption of our own grain, and did them no great prejudice; it hindered not their work, neither did it take away their senses, nor cost them much money.”

This petition, like the last, seems to have been of no effect, for we find these “destructive” drinks, brandy, coffee, tea, and chocolate, still in use in this country, and not yet prohibited by law.{119}

Arriving now at a period where the ancient gives way to the comparatively modern, this chapter necessarily ends. In the laws of the present day relating to ale and beer, are curiosities by the score; but we should hardly earn the thanks of our readers for devoting half this book to matters which are common knowledge. Suffice it to quote a verse from the lays of the Brasenose College butler, written, doubtless, at a time when it was first proposed to repeal the old beer tax, and which tells in simple words the probable result:―

Yet beer, they tell us, now will beMuch cheaper than before;Still, if they take the duty off,In duty we drink more.